I’m a queer, femme traveller. Here’s an honest telling of how my identity affects me abroad.

After an eighteen-hour bus ride, I’m finally plopped on a stool at a hostel bar nursing a beer in Medellin, Colombia. It’s humid and I haven’t yet showered. Beads of sweat run in rivulets down my temple and pool around my collarbone. A group of people sits down next to me. I smile politely, not quite ready to make small talk, but introduce myself anyway. They’re friendly. I start to relax and let my guard down. We’re getting along, sharing travel tips and itineraries. A British guy orders us another round. A French woman in a pink flowered sundress not unlike my own wiggles her eyebrows and leans in closer. “So, do you have a boyfriend?” she asks.

I pause, the lukewarm bottle of nondescript lager halfway to my mouth. I hate this question. Will my answer change what was starting off to be a good night?

I’m a lesbian. It usually comes up in the first conversations I have at hostels. I’m often the only queer person in a group of travellers. For safety reasons, I prefer to travel with other women that I meet at hostels. However, every time I do, I worry that they’ll think I’m predatory or hitting on them. After disclosing my sexuality, I’ve seen facial expressions change abruptly. I’ve been on the receiving end of uncomfortable silences and attempts to change the subject. I’ve been excluded from events just after outing myself. This makes travelling an isolating experience.

I’m also a femme. This can work to my advantage. I can pass as straight in most situations—a privilege which isn’t afforded to a number of my friends or partners based on how they look. That happens to be a privilege I’ve had to confront many times, in unexpected ways, while travelling.

When I travel, I have to choose when, where, and to whom I come out more so than when I’m at home.

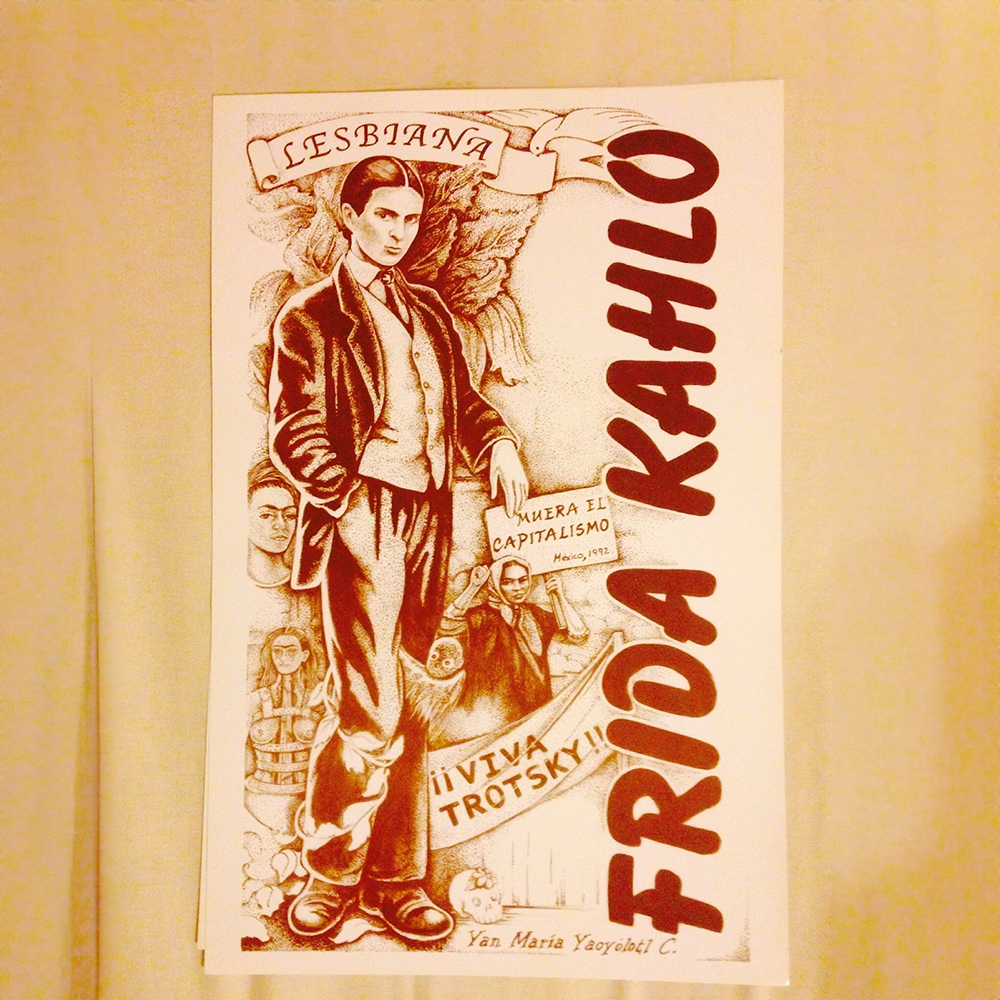

For example, I spent some time at Mujeres Creando, a Bolivian anarcho-feminist collective based in La Paz. I was younger, more naive, and I wanted to interview one of the founders—one of Bolivia’s only out lesbian activists.

She, rightfully, stared me down, scoffed, and said, “Why should I trust you? How do I know you’re really who you say you are? You can’t just waltz in and ask me questions about what it’s like to be gay in my country. You’ll never understand.” And she was right. My privilege protects me.

But identities are nuanced. My identity is nuanced. Especially when I’m someone who regularly transports myself into far-flung worlds, each with a new set of values, politics, biases, etiquette, and social norms. It’s complex.

Unless I’m walking down the street holding hands with another woman, most of the harassment I receive is due to misogyny, not homophobia. If someone discovers I’m gay, I find myself at the intersection of the two prejudices. Men will insist that they can “change” me, that I’m too pretty to be a lesbian, or that I just haven’t found the right man yet (occasionally, I’ll tell them that they probably haven’t found the right man yet either). They’ll sometimes touch me without my consent in an attempt to prove that if I just gave them a chance, I’d realize that I’m not a lesbian after all.

When I travel, I have to choose when, where, and to whom I come out more so than when I’m at home. That’s something that many femmes will recognize. Coming out isn’t a one-time thing, especially if you’re inclined to travel where you’re constantly meeting new people. We gauge each situation based on context and gut instinct to determine whether or not our safety will be threatened.

My radar can be off. Dancing at a club in Cochabamba, Bolivia, in my early twenties, a man wouldn’t stop flirting with me. Finally, I snapped and told him that I’m a lesbian. “No, you’re not,” he said with a smirk. I doubled down, confident that I was safe because my (straight) friends were with me. “Yes, I am. I have a girlfriend and I’m not interested in talking with you anymore,” I said. This only served to pique his interest. When I insisted on leaving the club, my “friends” became annoyed and rolled their eyes. I walked outside to wait for a taxi alone. The man followed me, begging for a threesome.

I’m constantly fetishized, even by other travellers who say they’re “cool” with it. When some men find out that I’m gay, they’ll either take that as an opener to ask me several personal and sexual questions or they will start treating me like “one of the guys.” What follows is usually some sort of effort to rope me into objectifying women with them. “You and I see women very differently,” I told a guy in Peru when he asked me which country had the women with the best butts. “I don’t participate in the dehumanization of my gender,” I informed a Czech guy when he wanted me to rate the other women in our group on a scale of one to ten.

We all noticed how even wearing something small with a rainbow on it was enough for some to be openly hostile in certain countries.

When I meet another lesbian at a hostel, I’m giddy to bond over shared experiences. In Quito, Ecuador, I met an Italian woman and her French partner, and we had a long heart-to-heart about what it was like travelling while queer. We all noticed how even wearing something small with a rainbow on it was enough for some to be openly hostile in certain countries. It’s exhausting hiding such a big part of who you are all the time. It’s exhausting changing the gender pronouns in your stories so you’ll sound straight. I lie about having a boyfriend or a husband all the time. Every time I do, a little piece of me withers. Hiding such a core aspect of myself always comes at a price.

When I travel with a partner, things can get dicey. We often have to pretend we’re just friends, careful not to show too much affection. People stare, judge, and occasionally comment and then the same questions run in circles through my mind: “Is that person slowing down in their car going to jump out and hurt us? Is this person going to call me a slur? Do I need to be ready to defend my date or friends?” I’m constantly on edge.

I’ve been told to stop holding my partner’s hand because a restaurant/medical clinic/sidewalk is a “family environment.” I’ve exchanged panicked looks with a partner while hitchhiking when one called the other by a pet name and the driver noticed. When we book accommodation, we always face the question of whether to book one bed or two. Sometimes, it’s not worth the hassle of explaining that we want to share, so we suck it up and pay a few extra dollars. It’s othering.

Sometimes, coming out sparks the silliest and most absurd of conversations. I met a group of rowdy Australian men on a two-day longboat in Laos. We got on the subject of dating after one had fallen in love at first sight with a Laotian woman. They asked if I’d seen any cute guys. After I told them I was gay, they shook their heads. “Why are you even trying to date in a country like this?” They chuckled in between swigs of beer. “Why are you?” I retorted. “I should be able to at least try to date anywhere I want!” They laughed. “Touche, mate!” one of them said before rattling off a list of all of the gay women he knew back home. Apparently, there’s a cute firefighter in Melbourne I have to meet.

Sometimes, it’s heartwarming. I got to hold a new friend’s hand at his first-ever pride parade in his conservative home country when he still hadn’t come out to his parents and was terrified to do so. It was a very special pride, as gay marriage had been legalized in that country just days prior. In India, I had the opportunity to learn about hijra (third-gender, often trans people, who occupy an important place in Hindu culture). In Malaysia, I found a nondescript queer bookstore tucked away in an office building and I excitedly bonded with the cashier. I’m always looking for queer spaces. I befriended the bartender at a hostel in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic who was ecstatic to meet another gay person and took me to a series of underground gay bars in the city. In Mexico, I found a gay bar in the Yucatán and winked at the door girl. She winked back. That little jolt of recognition, of similarity and connection, is one of the most rewarding and intimate parts of travelling while queer. I’m still in touch with a handful of these people today.

When I do choose to talk about this layer of my identity, I take the space I need. That we need. People make homophobic and transphobic jokes around me all the time before they know I’m a lesbian. It’s astounding what people say when they think they don’t need to be politically correct. As a white, middle-class, young, conventionally attractive woman, I’m in a position to stand up for my fellow queers and challenge people on their preconceived notions or harmful rhetoric. I can put a face on homosexuality that challenges views.

It’s astounding what people say when they think they don’t need to be politically correct.

Many people aren’t out in the countries I travel to. As a traveller, dating apps are solutions to get a handle on the local gay scene and know where to go (oftentimes, queer spaces keep a low profile to remain discreet). These apps are a good entry point to make friends and connect with a subculture that does its best to stay barely visible in certain parts of the world.

I met a woman on Tinder who’d worked at every gay bar in the city. She introduced me to her friends, and I was instantly plugged into a side of queer culture that I didn’t even know existed in that city. It’s such a relief to befriend or date other queer people you might not have thought twice about in your home country. My scuba diving instructor in Borneo told me what it was like being the only gay female instructor on the island. My date in Ecuador told me what it was like to be the only gay female clown (actually) in the official clown association (yes, I’m totally serious). People that I’ve dated have given me great insight into what it’s like to grow up— and subsequently come out—as a lesbian in conservative countries. I’ve learned about queer culture all over the world, and I wouldn’t have had that pleasure had I not been queer myself. When we find each other, it’s like coming home. It’s instant camaraderie.

Travelling has made me more confident in my sexuality than ever before because abroad, I constantly have to think about it. Back home, it’s just another fact about me, like having red hair or enjoying Texas barbecue. I’ve been out for a long time. I’m proud to be who I am and extraordinarily lucky to have a supportive family; homophobia exists everywhere, including where I come from. However, because of travel, I think more deeply now about the things that we have to do to stay safe as queer people, the concept of chosen families, the fact that the amount of lesbian bars is dwindling worldwide. I think about the space we have to carve, sometimes with a dull knife, to exist in a world still largely hostile to people like us.

I think about the space we have to carve, sometimes with a dull knife, to exist in a world still largely hostile to people like us.

The world has come a long way for LGBTQ+ rights. Tolerance, however, is different than acceptance. Rights are being rolled back in plenty of places once thought of as progressive. Discrimination occurs in every country, but certain places might have legal restrictions or issues you might not have considered. After a discussion with many other lesbian travellers, the overwhelming majority confirmed that the treatment of gay people is the number one reason why they would or wouldn’t visit a country.

For my fellow gay and trans travellers, I recommend joining many groups on social media to ask questions before you go somewhere. On the ground, the reality of what it’s like for gay people might be different than what you read on equality indexes (though that’s always a good place to start). Figure out how public displays of affection are received and personal experiences with hate crimes abroad. Scour for first-person accounts of what it’s like to be a lesbian in those countries. Will you need a VPN in case that country has blocked gay websites or apps? Is there state-enforced censorship? How discreet will you have to be?

When I mentioned to some family and friends that I was writing this essay, I was met with more arched eyebrows than I’d expected. “Why would travelling as a lesbian be any different than travelling as a woman?” They pondered. “Why does it have to be a separate topic?”

There are unique hurdles to overcome while travelling as a femme. I haven’t ever read an essay where I felt seen in that regard. Visibility is huge. That’s why I’m writing this. If I can help any of my fellow femme lesbians feel seen, even just for a second, every experience I’ve had has been worth it.

And if any cute firefighters from Melbourne want to slide into my DMs on Instagram, that’d be great.

Issue 5